Victory! VE Day Celebrations on the British Home Front

Article by Ian Whitehead.

This article was first published in the Centre’s Journal ‘Everyone’s War’ Issue 11: VE Day Anniversary Issue.

Ian Whitehead, from the University of Derby, drew upon the Centre’s holdings for an article on the Home Front in the Centre’s Journal: ‘Everyone’s War’, Issue 6: Home Front Issue (an abridged version of which is available here on the Centre’s website). Here his focus is narrower but his range of source material wider. Dr. Whitehead has an established reputation in published work on the British Army medical services in the two World Wars.1

The unconditional surrender of Germany was public knowledge on 7 May 1945. Sir Montague Burton, writing to his son, perceived a collective sigh of relief at delivery from danger, combined with a strong sense that this had been a victory worth fighting for:

Transcript of Letter

Montague Burton’s letter to his son, Raymond, serving overseas.

MONDAY 7TH MAY – 7 p.m. The unconditional surrender of Germany is announced. There is a sigh of relief everywhere that the nightmare is almost over and there is considerable satisfaction that the evil men who have perpetrated the ghastly deeds are receiving, or are likely to receive, punishment to fit their crime. We were here at Branksome in 1940 – just five years ago – when Belgium, Denmark, Holland and Norway were invaded. You were with us part of the time. It seems appropriate that we should be here when the liberation of those countries is announced. Never has so much history been crowded into so few days: in fact, I do not think history has so exciting and sensational a parallel. Three important figures – two who have brought more sorrow than any other two men previously [Hitler and Mussolini] and one who has done probably more than any single individual for the survival of civilisation in the hour of peril [Roosevelt], have been moved from the world’s stage within a few weeks. We are living in unprecedented times. Most people feel deeply grieved that Roosevelt was not spared to help frame the peace: his guidance and wisdom will be sadly missed. There is hope that Stalin will permit Vladivostock to be used as a base to bomb Kobe, Tokyo, and other Metropolitan towns of the Mikado; in any event, the war in the Far East might be over this year.

These were indeed momentous events and Burton was surely not alone in his conviction that he was living in ‘unprecedented times’. Certainly, Britain’s wartime leaders were conscious of the occasion and were eager to mark the final delivery from danger. King George VI and the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, were determined that 7 May 1945 should be celebrated as Victory Day. A nation that had stood alone, in 1940, in the face of Hitler’s seemingly invincible forces, could at last celebrate both its survival and its vital contribution to the defeat of Nazism. But, Churchill and the King were frustrated by the difficulties of co-ordinating the moment of victory with Britain’s principal allies, the United States and the Soviet Union. The King’s diary indicates his personal disappointment, as well as that of his government, at the delay in proceedings: ‘The P.M. wanted to announce it but President Truman and Marshal Stalin want it to be announced tomorrow at 3.0 p.m. as arranged. The time fixed for Unconditional Surrender is Midnight May 8th. This came to me as a terrible anti-climax, having made my broadcast speech for record purposes with cinema, photography and with no broadcast at 9.0 p.m. today!’2 In the moment of victory, Britain’s increasingly junior status in the wartime Big Three was, perhaps, becoming clear.

Unaware of the reasons for the delay, a young ATS clerk recorded the mixture of excitement and impatience that pervaded her office:

The war is over – that’s obvious – but when is Churchill going to say so? Everyone gives his opinion – ‘At nine’ – ‘not till tomorrow’ – ‘At midnight’. Normally, the office is clear by 5.55, but tonight every single member of staff stays to hear the 6 p.m. news – and still it is the same.’ 3 Without any official word, however, the people had already begun to celebrate. London, in particular, witnessed spontaneous gatherings of revellers and Union flags began to be draped from people’s windows. The ATS clerk joined the ‘fairly dense’ crowds and found that the capital was ‘really getting into the Victory mood, without waiting for Mr Churchill …. Trafalgar Sq. is gayer than ever, dancing and singing, the ‘Marseillaise’ and ‘Knees up Mother Brown’. The Palais Glide in the Haymarket, and little bonfires on the pavements fed by newspapers. Then – Piccadilly Circus again. It is dark now, no street lights and few lighted windows. But it is one mass of yelling, laughing, singing, shrieking people; a small sports car is trying to wriggle through, and its folded roof is in shreds. A brilliantly lit bus is bogged down beside Eros, with people swarming all over it, inside and out.4

But, although the party had already started for some, it was the next day, 8 May 1945, which was designated VE Day, with 9 May also declared a public holiday.

VE Day was a day for national rejoicing. The people celebrated victory in the ‘People’s War’. Yet, as Ernest Bevin observed,5 it was also a day that belonged uniquely to one individual – Winston Churchill. His radio broadcast at 3 p.m. brought the nation together. Later, MPs from all sides greeted him with great enthusiasm, when he arrived in the House of Commons. As so often during the War, Churchill captured the mood of the nation. This was a time to be thankful for survival, for freedom from the threat of bombs and for the victory of democracy over tyranny. His address to the Commons concluded with a call to proceed to St Margaret’s Church, for a thanksgiving service. Churchill gave specific mention to the wartime plight of the Channel Islands. Izett Croad, on Jersey, recorded the impact of his broadcast, which was relayed via public speakers:

The [Royal] Square was full of people wearing red, white and blue rosettes. There was absolute silence when Mr Churchill began his speech. When he spoke of the ‘dear Channel Islands’ there was a loud cheer. as he finished, the Union Jack was hoisted …. together with the Jersey flag and I can’t tell you how we felt. Then the Bailiff made his speech and told us that a British naval force was on the way, at which the cheers were deafening, that there was no longer any ban on wireless sets (more cheers) and that all prisoners would be free by tomorrow. After which we sang ‘God Save The King‘.

Emma Le Feuvre, who was also on Jersey, remembers an ‘indescribable’ feeling of freedom that those of her generation would never forget. For Tony Bougourd, an evacuee from Guernsey, marking VE Day in Lancashire, the day meant, above all, relief that ‘our home was free at last. All we wanted was to get back there’. Liberated from German occupation, and at last in receipt of much-needed food and medical supplies, the Channel Islanders had reason indeed to share in Churchill’s call for thanksgiving.

The islanders gave vent to a tremendous sense of release. After hearing the King’s speech, Izett Croad cracked open a bottle of champagne, which had been kept during ‘five long years’ of anticipation. Emma Le Feuvre writes, ‘flags and cameras, which had been hidden suddenly appeared! All that week we were on duty [with the St John’s Ambulance] at the Harbour to welcome the troops who were carried shoulder high amid cheers. Many people fainted through lack of food and excitement.’

As well as thanksgiving, it was also a time for fun. On the mainland, the Board of Trade relaxed wartime restrictions, allowing red, white and blue bunting to be bought off ration for the rest of May. Meanwhile, Churchill’s interest in beer supplies had elicited reassurance that London’s pubs would not run dry on the big day.6 It was just as well, as the capital was definitely in the mood for a party. C. J. Smith writes that if the churches were packed then so too were the pubs.

Huge crowds followed Churchill throughout the day eager to catch a glimpse of him as he criss-crossed Whitehall. He was cheered loudly when he appeared on the balcony of the Ministry of Health, and again later when he joined the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace. The King and Queen appeared at least eight times on the Palace balcony, greeting the enthusiastic crowds, which at one point numbered amongst them their own daughters, enjoying a rare moment of anonymity in the good-natured throng.

As the day progressed, increasing numbers of merry-makers spilled onto the capital’s streets. F. M Cooper, a lorry driver for the railways, recalled having to negotiate the packed thoroughfares of the West End:

The noise was deafening with people cheering. All the traffic was at a crawling pace. Suddenly, a crowd of Yanks jumped on the van. I could hardly see through the windscreen. They were everywhere insisting I take them to Pont Street, which was off my round, but the only thing I could do was to take them. When I got there, they wanted me to join their party, but as I shouldn’t have been there, I refused. After work… I celebrated by going to Piccadilly Circus and Trafalgar Square where there were thousands of people.

Jean Dunbar, an Australian married to a British officer in the Royal Artillery, was one of those who joined the multitude. Her diary proudly records her participation in the day’s events:

Heard Mr Churchill’s official announcement of Germany’s surrender before going out. We started our official tour at Piccadilly Circus which was a focal point for the crowd. From there we made our way on foot to Leicester Square, Trafalgar Square and down Whitehall arriving abreast of St. Margaret’s just in time to see part of the House of Commons procession returning from Thanksgiving service. We went into the Abbey for the end of a short service. Afterwards, we made our way up the Mall to the Palace which was the culmination of our tour. Saw the Royal family, accompanied by Mr Churchill when they appeared on the balcony. Afterwards we saw Mr Churchill quite close as he left the Palace. My last gesture … was to remove my identity bracelet. A stirring day – I was glad to be in London.

Transcript of Diary Page ( right)

MON 7 . Got up for work [?] when we came home at night they announced it on the radio that the War in Europe was over.

TUES 8 . Today is VE Day and tonight we all were invited to the Motheringham Drome dance and I had a bang on time.

WED 9 We got up [?] and went to Boston at night went to the Dance at Billingham had a lovely time.

Elsewhere, there were similar scenes. ‘How we celebrated!’ wrote Joyce Markwick of the day’s events in Ashford, Kent: ‘The bells rang and the lights came on – no more creeping about in the blackout!‘

After church service to thank God for deliverance, crowds danced in the High Street until nearly dawn.’ In Leeds, Jean Barker witnessed the scene from the top deck of a tram: What a sight, everyone was dancing [around the town hall], soldiers, sailors, airmen, WRACS, ATS and WRENS. Thousands of them all going crazy.’

For the most part, however, events in provincial towns and cities were lower key than those in the capital. There were few organised civic events on the day and the inhabitants lacked the focus of national figureheads, which the London crowds enjoyed. Amy Briggs went into Leeds to attend a service at midday. Her diary records her disappointment: ‘no service! Thanks to bungling of notices and broadcasts everyone mixed up and standing about in dismay. Left Hall, didn’t know what to do. Badly wanted Sheila [her daughter] to remember VE Day but nothing happened to make any impression on her.’ In Manchester, William Whitehead recalled being taken to Piccadilly Gardens. People were singing and cheering but here, too, they ‘just appeared to be milling about’ and nothing happened to leave a big imprint on the mind of a twelve year old boy.

More powerful childhood memories were forged by the street parties, which were organised in local communities across the country. Irene Bain’s account of events in her street, in Mitcham, is typical of so many:

A group of women in the street formed a committee to organise [the party]. On the actual day trestle tables were set up down the centre of the road and covered with cloths. Chairs were brought out of the houses and arranged down each side. Use was now made of the precious items of food hoarded for just this purpose. Vases were filled with flowers picked from our gardens and set at intervals down the tables, which were soon laden with plates of food. All of us children went to the party with our brothers and sisters, and the babies were carried along too. I wore my best dress and the recently bought wooden soled sandals I was so proud of… At the end of the party one of only two car owners, a taxi driver, sat at a little table and handed out to each child in the road a sixpence.

Comment on A VE Day street party for children of Brookside Avenue, Southampton.

‘Mothers had been collecting packets of blancmange and jelly for weeks and saving up all the dried milk and dried egg powder that could be spared. We burned an effigy of Hitler in a torn wicker chair that came from our back garden’. [Patricia Land].

Shirley Cheves, who spent her childhood in wartime Lincoln, was also smartly dressed for the party she attended:

I wore my red parachute silk dress with the blue and white braid and we all had our photograph taken together.’ A teacher, in Thornaby-on-Tees, wrote that ‘people have gone to great trouble to give enjoyment to their children – red, white and blue dresses (I see three beautifully made from bunting, the children being sisters), decorated tricycles, toy motor cars. Most dogs have bows and horses are gay too.7

People dug out their Coronation decorations to festoon the streets and houses. However, in Thornaby’s case, as for many others, the British weather did not smile on outdoor celebrations, which were postponed for later in the week.

C J Smith writes that bombing had taken its toll on the many ‘pot-holed or debris littered’ streets of West Ham. In his road only thirteen houses had survived out of two hundred. Street parties were thus not a practical option. The young, however, did not let this stand in the way of having some VE Day fun:

We street urchins now in our early teens and having graduated in inventiveness through our Blitz-education, were determined to make up for lost time and at least four ‘Guy Fawkes Nights’, by having the ‘mother and father’ of all street bonfires. Achieving this was made easy for us by the abundance of wood from the bomb wrecked houses plus three horse-drawn haulage carts from the nearby ‘Fox’s Hauliers’ yard, whose stables had been completely devastated and all its horses killed or badly injured in a frightening and unforgettable night raid …. [The amount of wood] gave us a bonfire which burnt for about three days and threatened to cause as much damage to the street as had the Germans, before the Auxiliary Fire Service came and doused our flames of victory. The thing I remember most about that bonfire was the pyrotechnics we discovered …. [we] used the large sheets of asbestos that the war-damage-repair building teams had used after the 40/43 Blitz but had been rendered surplus to requirements when the V-1s and V-2s returned to finish the aerial destruction of our homes. By chance we found that if a fairly large piece of asbestos sheet was laid directly over the fire then, within minutes, it would explode with a large bang, the inherent danger of this was completely lost on us carefree lads.

Street celebrations were certainly not just for the children. D E Williams records ‘a piano [being] dragged into our crescent and our parents acting like big kids again.’ Particularly embarrassing for the children were the choruses of ‘Knees up Mother Brown’, with high-spirited mums, aunts and grandmas revealing long knickers that reached down to their knees. Irene Ban wrote that the evening celebrations were devoted to the adults and remembered watching their antics with some amazement: ‘There was quite a gathering …. with a gramophone playing and dancing going on. A plump, elderly lady of staid and sober habits, whom I knew from church and was a little in awe of, had on a smart new dress for the occasion. I was so surprised to see her leading the line in the conga.

A soldier father writes from the Lebanon to his daughter in Lincoln about the excitement there on VE Day and of his hope soon to be home. [Shirley Cheves]

A soldier father writes from the Lebanon to his daughter

FROM DADDY AT TRIPOLI, LEBANON

Shirley Darling

Well dear at last the war is over with Germany & before many months are over I hope to be home with you for good dear & that’s going to be a great day for us all darling. I expect you have been having a lot of excitement at Lincoln & I want you to write & tell me all about it dear. I am writing to Clive as well in this letter dear so when you have read this you can read his to him darling. I hope by now you have received [Oddilles ?] letter & she is awaiting your reply and as soon as I get it I shall give it to her dear. I hope dear that uou are still being good & helping Mummy all you can & also darling I hope you are fully [?] shoulders back when you are walking. Give Clive a big kiss for me darling & so I think this is about all this time dear. so “NIGHT NIGHT” dear & now read Clive’s letter to him.

FROM YOUR LOVING DADDY

x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Shirley Cheves, mixed with the crowds on Lincoln High Street and, ‘saw a woman, I knew vaguely, being pushed along by a railway man on one of the flat baggage trolleys; she appeared quite drunk and was waving a small Union Jack.’

Most children, naturally, enjoyed the parties. Clearly, there was amusement, and as described sometimes embarrassment, at the antics of adult revellers. There was also an element of bemusement – the younger ones had no memory of what peacetime had been like, so the real significance of the day was often hard to grasp. On asking what peace was like, Barbara Chamberlain was informed ‘that it meant having ice cream and oranges, bananas and chocolate bars, lights in the streets and everyone being safe. And best of all, Daddy being home again.’

But, although Joyce Markwick records the period as ‘a time of great joy,’ this was not the case for everyone. Unlike Barbara Chamberlain‘s dad, thousands of fathers would not be coming home. Not surprisingly, therefore, the response to VE Day by many families and communities was much more muted, as Jean Barker makes clear:

Many neighbours and school friends lost brothers, sisters, sons and fathers in the war. My classmate Betty Edwards lost a brother in Norway; Albert Knowles who lived on our street was also killed in the Navy. Mrs Audsley’s son was drowned in the hold of a Japanese prison boat when the British bombed it. Mrs Hen lost her boy in a mantrap in Burma …. Things were never the same after the war with half the family gone [her brothers, Alan and Arthur]. When peace was declared [we didn’t have a street party], maybe our neighbours thought we hadn’t much to celebrate.

Even families where the father did return were not always able to join in the fun. Amy Briggs‘s husband had been invalided out of the army and things were evidently difficult for them. After arriving home on 8 May, disappointed that Leeds city centre had offered no organised entertainment to divert her young daughters, she found her husband ‘stretched on [the] settee reading. No word spoken. Has not spoken to me for three weeks – don’t know why – but feel that if he won’t speak on VE Day, he’ll never speak! Simply couldn’t bear it. Rushed round to Mrs M. with Anne. Had a cry and then a lump of her apple pie and talked until 1 a.m. Made some tea when I went back home. No word from T. [her husband]. God! What a day. Wish I were back at work with my friends!’8

For others, there was as yet no end of the War in which to rejoice. Mrs J Garvey was:

Personally still filled with dread as my future husband was training for the assaults on Japan on VE Day.

The fact that Japan still had to be defeated provides an understandable explanation of why, in spite of all the celebrations, 8 May 1945 did not really recapture the excited mood of 11 November 1918: ‘Several people today have said that as they had relations in the Far East they could not celebrate properly. That has been in everyone’s heart that more fighting, more dying and more atrocities are still to come. Also that all the flag waving and dancing will not bring alive the dead to their homes. Men that have lost their sight and limbs cannot be the same. Life will always be sadder for those of us who think. If we knew this had been a war to end war we would feel more jubilant but when it may happen again without extreme care, it makes life seem a dilemma.9

William Whitehead writes that his memories of VE Day are quite vague, he simply recalls sitting, with other children, round a fire in the street, listening to a neighbour playing the accordion. Families in his street still had sons away on active service – it is VJ Day that is therefore clearer in his mind:

All the grown ups in the road had organised a street party for us. They had obtained trestle tables from somewhere and they had made tablecloths out of Union flags, someone had made bunting and stretched it across the road by tying it to the lampposts. We children did not realise the sacrifices the adults had made to enable them to put on the spread of food…every child [also] received a white mug that had their name and the letters V.J. and the date on them.

On 8 May, nobody knew that these VJ celebrations were close at hand – the general view was that there would be at least another year of hard fighting.

In addition to continued hostilities, the edge was also taken off the festive mood when the realities of the War’s horrific events became more widely known. C J Smith writes that his ‘most poignant memory of the weeks following VE Day and which appeared to have a marked effect on most people that soured the taste of victory, was the graphic news of the Holocaust. Everyone was encouraged to go to our one and only working cinema – the ‘New Imperial and see the shocking film footage coming out of Germany’.

He recalls that these images made people physically sick as they stared disbelievingly at the Nazi atrocities, making them realise that ‘our deprivations caused by the almost nightly bombings and our food, shelter and clothes shortages, were nothing.’

Uncertainties about the post-war world also clouded the mood and left people unsure in their reaction to victory. On 9 May, Amy Briggs wrote that everyone was ‘looking considerably more cheery than they did on V-Day. I think we were all too stunned when peace did come and did not know what to do with ourselves. To me people just looked like a lot of sheep drifting around town [V-Day in Leeds] all looking for someone else to stand on their heads and shout Whoopee’ but no one did. Truly they were a subdued, happy mass, lost and off their bearings because all at once their best ‘toy’ had been taken from them – the war!’10

The people also became aware, if they were not already, that peacetime life was not going to bring an immediate deliverance from wartime hardships and austerity. C J Smith recalled that ‘the cupboard was bare as we rejoiced in the euphoria of victory [and] there came the stark realisation that the country had suffered and, as a result, the belts which we were told to tighten in those bleak days of war, would not be relaxed as shortages of almost everything remained. The cinema and theatre lights which had dazzled us all on VE night had been switched off again in order to save fuel. There was less meat in the shops than there had been the year before.’ Rationing had, even yet, not reached its peak. Bread, for example, not rationed during the War, was added to the Ministry of Food’s list in 1946.

By 17 May, the young ATS clerk, who had so enjoyed the victory celebrations, was noting a decisive change in mood, affected more by international than home concerns:

It is little more than a week since VE day, but already the reaction is setting in. I find the news extremely depressing. Britain and the US seem to be at loggerheads with the USSR over nearly every controversial point, and the US isolationist press, in its usual unhelpful way, is fomenting this state of affairs … There seems to be nothing but strife and confusion ahead when we should be seeing the bright skies of peace – and we are all feeling tired and hardly capable of coping with it.11

The peacetime continuation of rationing was emblematic of the economic challenges that confronted the post-war government, as it worked to rebuild the war-scarred nation. The deteriorating relationship with the USSR became the major defence and foreign policy concern. However, these domestic and international matters were to exercise a new premier and a new administration. Unlike Lloyd George’s government, in 1918, the Churchill Coalition did not extend beyond the War – indeed it did not survive to see the end of it. The resumption of normal political life caught many people by surprise, as the following account exemplifies: ‘I came back to the world of newspapers and radio today, after three days of blissful isolation in a Norfolk village. I found a state of political upheaval, Parliament in the act of being dissolved, and Churchill and Attlee being rude to each other in public letters.’12 The 5 July election, and its apparently unexpected result (a Labour landslide announced on 26 July), signified the extent to which the British in 1945 were much more focused on building the peace than celebrating the victory. There was a sense that the missed opportunities of 1918, real or imaginary, must not be repeated. Jobs, homes, health and education were uppermost in people’s minds.

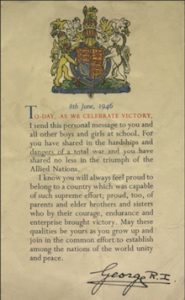

Transcript of Letter (Right)

H.M. King George VI’s message to schoolchildren.

8th June, 1946

TO-DAY AS WE CELEBRATE VICTORY, I send this personal message to you and all other boys and girls at school. For you have shared in the hardships and dangers of a total war and you have shared no less in the triumph of the Allied Nations.

I know you will always feel proud to belong to a country which was capable of such supreme effort; proud, too, of parents and elder brothers and sisters who by their courage, endurance and enterprise brought victory. May these qualities be yours as you grow up and join in the common effort to establish among the nations of the world unity and peace.

George R.I.

Outwardly, there were many similarities between 8 May 1945 and the Armistice celebrations in 1918: the vast crowds, the feteing of the Prime Minister, the cheering of the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace. It is also the case that people had plenty of reason for mixed emotions on both occasions.13 However, there are also considerable differences. There was much more euphoria in 1918. Victory and the end of hostilities generally surprised people. In 1945, victory had been trailed for months and celebrations kicked off before an official announcement had been made. In 1918, the British genuinely believed that they were marking victory not just over Germany, but over war itself. Few in 1945 were so optimistic, especially given that, on VE Day, the present war had not yet reached its end. Above all, in 1945, there was little reason to suppose that peace would be easy – building a better Britain at home and defending Britain’s interests overseas were immense challenges. As A J P Taylor observed, ‘Few Englishmen now imagined that victory was itself a solution, an end of all problems and difficulties.’14

VE Day was an opportunity to let off steam. It was an end to bombings and blackouts. Hitler was dead, burning in effigy on bonfires across the land. The British nation was secure – the mainland had withstood all threat of invasion and the Channel Islands were liberated. But joy at these events did not blur the nation’s vision. There was no wallowing in victory and no complacency. There were too many ongoing worries and doubts to lend the day any greater significance. Perhaps these concerns (along with knowledge that the hopes of 1918 had been disappointed) explain why surprisingly few of the vast number of individual accounts, preserved in the Second World War Experience Centre, make significant mention of VE Day. For most people, it was a resting point, not the final destination. The King’s diary entry for 8 May makes plain his own appreciation of the realities, in words that the vast majority of his subjects are likely to have echoed: ‘The day we have been longing for has arrived at last and we can look back with thankfulness to God that our tribulation is over. No more fear of being bombed at home and no more living in air raid shelters. But there is still Japan to be defeated and the restoration of our country to be dealt with, which will give us many headaches and hard work in the years to come.’15

Endnotes

1. Unless otherwise indicated, all references in this article are to papers held at the Second World War Experience Centre, Leeds.

2. Diary of HM King George VI, cited in Peter Hennessy, Never Again: Britain 1 945-1951, Vintage, 1993, p. 57.

3. Dorothy Sheridan [ed], Wartime Women: A Mass Observation Anthology, Mandarin, 1991, p. 230.

4. Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 231.

5. Hennessy, Never Again, p. 61.

6. Hennessy, Never Again, p.59.

7. Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 238.

8. Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 228.

9. Sheridan, Wartime Women, pp. 245-246.

10.Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 228.

11.Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 236.

12.Sheridan, Wartime Women, p. 236.

13.For a thorough discussion of the mood and emotions of November 1918 see Peter Liddle’s chapter, ‘Britons on the Home Front’ (Chapter 5), in Hugh Cecil & Peter H Liddle, At The Eleventh Hour, Leo Cooper, Barnsley, 1998, pp. 68-83.

14.AJ P Taylor, English History 19 14-1945, Oxford, 1965, p. 594.

15.Diary of HM King George VI, cited in Hennessy, Never Again, p. 60